|

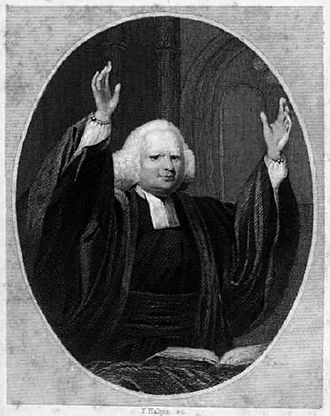

George Whitefield

|

|

|---|---|

|

Portrait by Joseph Badger, c, 1745

|

|

| Born | 27 December [O.S. 16 December] 1714 |

| Died | 30 September 1770 (aged 55) |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Oxford |

| Signature | |

George Whitefield (/ˈhwɪtfiːld/; 27 December [O.S. 16 December] 1714 – 30 September 1770), also known as George Whitfield, was an Anglican cleric and evangelist who was one of the founders of Methodism and the evangelical movement.[1][2]

Born in Gloucester, he matriculated at Pembroke College at the University of Oxford in 1732. There he joined the “Holy Club” and was introduced to the Wesley brothers, John and Charles, with whom he would work closely in his later ministry. Whitefield was ordained after receiving his Bachelor of Arts degree. He immediately began preaching, but he did not settle as the minister of any parish. Rather he became an itinerant preacher and evangelist. In 1740, Whitefield traveled to North America where he preached a series of revivals that became part of the “Great Awakening“. His methods were controversial, and he engaged in numerous debates and disputes with other clergymen.

Whitefield received widespread recognition during his ministry; he preached at least 18,000 times to perhaps 10 million listeners in Great Britain and her American colonies. Whitefield could enthrall large audiences through a potent combination of drama, religious eloquence, and patriotism. He used the technique of evoking strong emotion, then using the vulnerability of his enthralled audience to preach.[3]

Early life[edit]

Whitefield was born on 27 December [O.S. 16 December] 1714 at the Bell Inn, Southgate Street, Gloucester. Whitefield was the fifth son (seventh and last child) of Thomas Whitefield and Elizabeth Edwards, who kept an inn at Gloucester.[4] His father died when he was only two years old, and he helped his mother with the inn. At an early age, he found that he had a passion and talent for acting in the theatre, a passion that he would carry on with the very theatrical re-enactments of Bible stories he told during his sermons. He was educated at The Crypt School in Gloucester[5] and at Pembroke College, Oxford.[6][7]

Because business at the inn had diminished, Whitefield did not have the means to pay for his tuition.[8] He therefore came up to the University of Oxford as a servitor, the lowest rank of undergraduates. Granted free tuition, he acted as a servant to fellows and fellow-commoners; duties including teaching them in the morning, helping them bathe, cleaning their rooms, carrying their books, and assisting them with work.[8] But, Whitfield would later confess that though he did good works and tried to obey the law of God, he was not yet truly converted to Christ. It was Henry Scougal‘s book, The Life of God in the Soul of Man, that Whitfield says opened his eyes to the Gospel and led to his conversion. It was that book he says, that God used to show him that he was still lost despite all his attempts to gain the favor of God by means of good works. Only by God’s grace can a person realize they have offended God and their need for Jesus Christ, God’s Son, and His righteousness imputed to them by faith. Henry Scougal’s book showed him the need for a man to be born of God from above, and that this is a supernatural work of the Holy Spirit creating a new heart and a new nature within that wants to serve God, not in order to be saved, but because one has been graciously and undeservedly saved. In 1736, after Whitfield’s conversion, the Bishop of Gloucester ordained him a deacon of the Church of England.[1]

Evangelism[edit]

Whitefield preached his first sermon at St Mary de Crypt Church[2] in his home town of Gloucester, a week after his ordination as deacon. The Church of England did not assign him a church, so he began preaching in parks and fields in England on his own, reaching out to people who normally did not attend church. In 1738 he went to Savannah, Georgia in the American colonies as parish priest[citation needed] of Christ Church, which had been founded by John Wesley while he was in Savannah. While there Whitefield decided that one of the great needs of the area was an orphan house. He decided this would be his life’s work. In 1739 he returned to England to raise funds, as well as to receive priest’s orders. While preparing for his return, he preached to large congregations. At the suggestion of friends he preached to the miners of Kingswood, outside Bristol, in the open air. Because he was returning to Georgia he invited John Wesley to take over his Bristol congregations and to preach in the open air for the first time at Kingswood and then at Blackheath, London.[9]

Whitefield, like many other 18th century Anglican evangelicals such as Augustus Toplady, John Newton, and William Romaine, accepted a plain reading of Article 17—the Church of England’s doctrine of predestination—and disagreed with the Wesley brothers’ Arminian views on the doctrine of the atonement.[10] However, Whitefield finally did what his friends hoped he would not do—hand over the entire ministry to John Wesley.[11] Whitefield formed and was the president of the first Methodist conference, but he soon relinquished the position to concentrate on evangelical work.[12]

Three churches were established in England in his name—one in Penn Street, Bristol, and two in London, in Moorfields and in Tottenham Court Road—all three of which became known by the name of “Whitefield’s Tabernacle”. The society meeting at the second Kingswood School at Kingswood was eventually also named Whitefield’s Tabernacle. Whitefield acted as chaplain to Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, and some of his followers joined the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion, whose chapels were built by Selina, where a form of Calvinistic Methodism similar to Whitefield’s was taught. Many of Selina’s chapels were built in the English and Welsh counties,[13] and one, Spa Fields Chapel, was erected in London.[14][15]

Bethesda Orphanage[edit]

Whitefield’s endeavour to build an orphanage in Georgia was central to his preaching.[4] The Bethesda Orphanage and his preaching comprised the “two-fold task” that occupied the rest of his life.[16] On 25 March 1740, construction began. Whitefield wanted the orphanage to be a place of strong Gospel influence, with a wholesome atmosphere and strong discipline.[17] Having raised the money by his preaching, Whitefield “insisted on sole control of the orphanage”. He refused to give the trustees a financial accounting. The trustees also objected to Whitefield’s using “a wrong method” to control the children, who “are often kept praying and crying all the night”.[4]

In 1740 he engaged Moravian Brethren from Georgia to build an orphanage for negro children on land he had bought in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania. Following a theological disagreement, he dismissed them and was unable to complete the building, which the Moravians subsequently bought and completed. This now is the Whitefield House in the center of the Moravian borough of Nazareth, Pennsylvania.[18][19]

Revival meetings[edit]

Beginning in 1740, Whitefield preached nearly every day for months to large crowds as large as eighty thousand people as he travelled throughout the colonies, especially New England. His journey on horseback from New York City to Charleston, South Carolina, was at that time the longest in North America ever documented.[20] Like Jonathan Edwards, he developed a style of preaching that elicited emotional responses from his audiences. But Whitefield had charisma, and his loud voice, his small stature, and even his cross-eyed appearance (which some people took as a mark of divine favor) all served to help make him one of the first celebrities in the American colonies.[21] Like Edwards, Whitefield preached staunchly Calvinist theology that was in line with the “moderate Calvinism” of the Thirty-nine Articles.[22] While explicitly affirming God’s sole agency in salvation, Whitefield freely offered the Gospel, saying at the end of his sermons: “Come poor, lost, undone sinner, come just as you are to Christ.”[23]

To Whitefield “the gospel message was so critically important that he felt compelled to use all earthly means to get the word out.”[24] Thanks to widespread dissemination of print media, perhaps half of all colonists eventually heard about, read about, or read something written by Whitefield. He employed print systematically, sending advance men to put up broadsides and distribute handbills announcing his sermons. He also arranged to have his sermons published.[25] Much of Whitefield’s publicity was the work of William Seward, a wealthy layman who accompanied Whitefield. Seward acted as Whitefield’s “fund-raiser, business co-ordinator, and publicist”. He furnished newspapers and booksellers with material, including copies of Whitefield’s writings.[4]

When Whitefield returned to England in 1742, an estimated crowd of 20–30,000 met him.[26] One such open-air congregation took place on Minchinhampton Common, Gloucestershire. Whitefield preached to the “Rodborough congregation”—a gathering of 10,000 people—at a place now known as “Whitefield’s tump”.[27] Whitefield sought to influence the colonies after he returned to England. He contracted to have his autobiographical Journals published throughout America. These Journals have been characterized as “the ideal vehicle for crafting a public image that could work in his absence.” They depicted Whitefield in the “best possible light”. When he returned to America for his third tour in 1745, he was better known than when he had left.[28]